What to expect when visiting the Serapeum of Saqqara, from underground layout to granite boxes, Apis bulls theories, and practical advice.

You’re at Saqqara for the Step Pyramid, obviously. Many people take pictures, guides herd groups from one stone to the next, and everything looks more or less like you would expect.

Then there’s this other place, a short car ride away, that somehow gets skipped by most visitors, even though it’s right there and even though what’s inside is far stranger than anything happening above ground. The Serapeum of Saqqara is typically something travelers stumble into by accident, perhaps because an enthusiastic guide quietly mentioned it and people decided to trust them. That’s what did it for me, at least. You go down, the light and temperature both drop, and very quickly you’re walking through a long underground corridor lined with enormous granite boxes that seem far too precise and heavy.

I’ll give you just enough information to keep you curious, and not nearly enough to spoil what comes next: this is where the ancient Egyptians were believed to bury the sacred Apis bulls.

Origins, Purpose and Mysteries of The Serapeum

What it was meant to be

Saqqara was the main necropolis of Memphis, Egypt’s political and religious capital for much of the Old Kingdom. The nearby Step Pyramid of Djoser already marked the area as sacred and ritually charged.

So, on paper, the Serapeum was a burial place. Not for people, but allegedly for the sacred Apis bulls, animals believed to embody divine power. We know bulls in this region lived a pampered, ritual-heavy life and, once they died, got a burial that matched their status.

What makes the Serapeum different is how far that logic was taken. Instead of having regular chambers, the Egyptians carved out a long underground system and filled it with 24 massive granite sarcophagi, each weighing an estimated 80 tons, lids included. Every box was carved from single blocks of granite quarried hundreds of miles away at Aswan. If this was really about honoring bulls, it was done on a scale that feels excessive, even by Egyptian standards.

When it was built and rediscovered

The site was used and expanded over many centuries, beginning in the New Kingdom around the 14th century BCE, with major additions during the Late Period. This wasn’t a one-off project but something that evolved over time, which helps explain why parts of the Serapeum feel inconsistent.

By the way, the Pyramid of Djoser located nearby dates to around 2650 BCE. The earliest sarcophagi in the Serapeum appear roughly 2,000 years later: by the time the Apis bulls were being buried, the Step Pyramid was already ancient history.

After centuries of being sealed and forgotten, it resurfaced in 1851, when Auguste Mariette followed a partially buried avenue of sphinxes and reached the underground galleries. His excavation revealed the chambers, and the now-famous granite boxes, many of which were already empty when first opened. The discovery immediately raised questions that still haven’t gone away.

What complicates the story

Here’s where things stop being tidy. Despite the traditional explanation, no complete Apis bull mummies were found inside these specific granite sarcophagi. Some contained fragmentary remains, others were entirely empty, and a few held materials that didn’t clearly match the expected burial ritual. This detail comes up repeatedly in early excavation reports and is one of the most persistent points of debate surrounding the site. And the few Apis bull mummies that where discovered in the area, were resting in much simpler, and one could say more reasonably-sized, sarcophagi.

The gap between what the site is supposed to be and what was actually found underground is one of the main reasons it still attracts so much attention today.

Key Features To See At The Serapeum

The Gallery

One moment you’re in open desert, the next you’re going down a stairway cut straight into the rock, leaving daylight behind faster than expected. What’s inside is essentially a long underground gallery cut into the limestone bedrock, with side chambers opening off both sides. The main corridor measures roughly 300 meters in length and there are 24 granite sarcophagi in total, each placed inside its own side chamber.

These chambers were clearly carved to extremely tight tolerances, just large enough to receive a single box, leaving only a few centimeters of clearance on each side. Once a sarcophagus was slid into place, there was no realistic way to move it again without dismantling part of the structure.

One detail that immediately stands out by the exit is the presence of a granite box partially blocking the corridor itself, rather than sitting inside a side chamber. The box appears to have been moved there and never relocated afterward. The most widely accepted explanation is logistical: the box was likely being transported when something happened, and it was simply left there because moving an object of that size was no longer logical or possible.

Another important point is that not all chambers were used in the same way. Some show clear signs of having been sealed after placement, while others appear unfinished or modified later.

There are no decorated walls, no reliefs, no texts guiding the visitor. The focus is entirely on the architecture and the objects themselves. This was not meant to be seen, and certainly not meant to be understood at a glance.

The Granite Boxes

The boxes are carved almost exclusively from red granite quarried at Aswan, more than 800 kilometers south of Saqqara. Transporting blocks of this size that distance was already a serious undertaking. What they did with them once they arrived is where things start getting interesting.

Each box is roughly 4 meters long, 2.3 meters wide, and 3.3 meters high, with individual weights commonly estimated between 60 and 80 tons, including the lid. The surfaces are flat, squared, and sharply defined, including interior corners that are tricky to achieve without modern tools. The lids alone can weigh over 20 tons, yet they sit flush, with contact surfaces that look well finished.

The level of polish varies, but several boxes reach a finish close to mirror-like on their exterior faces. Some sarcophagi are completely plain, others bear hieroglyphic texts naming specific Apis bulls, pharaohs, or dates. There’s no consistent rule.

What was found inside is just as uneven. A few boxes contained fragments of bone, resin, or organic material consistent with burial practices. Many were empty when opened in the 19th century. No intact Apis bull mummy was ever found sealed inside one of these granite sarcophagi. That fact alone doesn’t invalidate their religious function, but it does raise questions about reuse, removal, disturbance, or changing ritual practices over time.

The Most Impressive Examples

Most sarcophagi in here are impressive, but two of them in particular are worth stopping longer for:

1. Ptolemaic Inscribed Sarcophagus with Empty Cartouches

The most visually striking sarcophagus in the Serapeum sits at the far end of the Greater Vaults and is dated to the late Ptolemaic period, associated with the reign of Ptolemy XII Auletes or Cleopatra VII.

This is the newest sarcophagus and the only one whose inscriptions remain largely intact. Its exterior surfaces are exceptionally smooth and finely finished. It’s the only one that has a dedicated staircase, allowing close inspection of the carved texts.

And yet, despite its level of decoration, the sarcophagus was never completed. The royal cartouches were left empty, making it impossible to confirm the identity of the Apis bull it was prepared for.

2. Amasis II Apis Bull Sarcophagus

By contrast, the sarcophagus dedicated under Amasis II represents one of the clearest and most securely identified examples in the Serapeum. Dating to around 550 BCE, it is explicitly inscribed for an Apis bull that died in regnal year 23 of the king’s reign, leaving little doubt about its original purpose. The coffer remains in its chamber, while the lid is no longer in place and is displayed near the entrance to the Greater Vaults, a separation already noted in early excavation records.

Visiting the Serapeum of Saqqara: Access & Tickets

The Serapeum sits inside the wider Saqqara necropolis, a short distance from the Step Pyramid, but most visitors don’t approach it independently. In practice, this area is best visited as part of a guided day trip from Giza, usually combining Saqqara with a stop in Memphis. That setup keeps things simple and avoids dealing with transport, ticket offices, and access issues on your own.

If you’re already planning a Saqqara visit with a driver or guide, adding the Serapeum is straightforward. It’s close, it doesn’t require a long detour, and it fits naturally into the flow of the day. You just need to ask explicitly before getting there. Many standard itineraries still skip it unless requested, even though it’s one of the most unusual sites in the area.

Access to the Serapeum requires a separate ticket from the general Saqqara entrance. Tickets are sold at the main Saqqara ticket office, not at the site itself, which is another reason to bring it up with your guide in advance.

As of 2026, the Serapeum of Saqqara ticket costs 600 EGP for foreign visitors. Prices in Egypt do change, sometimes without much notice, so treat this as a reference rather than a guarantee. The current price can usually be verified on the official government tourism website.

Inside, visits are self-paced but not long. Most people spend 20 to 30 minutes underground, longer if you stop often to look closely at the boxes or take photos.

The site opens at 08:00 am, with last entry at 04:00 pm. Arriving earlier improves your chances of having the place to yourself, but honestly, even on a high-season afternoon, you’re still likely to be mostly alone.

- Most first-time itineraries focus on the major highlights, which makes sense. 👉 I break those down in my 10 Best Places To Visit in Egypt for First-Time Travellers, and the Serapeum fits best once you’re already heading to Saqqara.

Is It Actually Worth A Visit?

If you’re already going to Saqqara, the Serapeum is an easy yes. It takes little time, requires minimal effort to add to a standard Giza–Saqqara–Memphis day trip, and delivers something genuinely different from the rest of the plateau.

This isn’t a site that amazes you through decoration or scale in the traditional sense, but what you get instead is archeology in motion and something truly unique to speculate on. For anyone even mildly interested in how ancient Egypt worked, rather than how it’s usually presented, that’s the appeal.

It’s probably not ideal if your priority is iconic visuals or if you’re rushing through Egypt ticking off highlights at speed. But if you enjoy places that feel slightly off-script, where the official explanation exists yet doesn’t quite close the case, the Serapeum is one of the most memorable stops you can make in Egypt.

Keep reading:

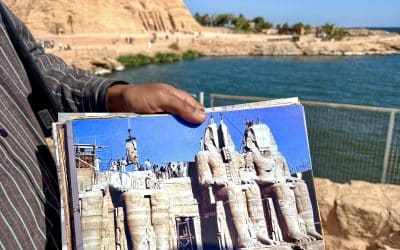

The Ancient Egyptian Temples That Had to Be Moved

Several ancient Egyptian temples were physically moved to survive modern dams. Here’s what was saved, what was lost, and how to read these famous sites today. [dssb_sharing_buttons icon_placement="icon" icon_width="fixed" alignment="left" icon_color="#000000"...

Valley of the Kings: Map, How to Visit & Best Tombs in 2026

A practical Valley of the Kings map and guide. Where it is, how to visit, tickets explained, and the most beautiful tombs to see first in Luxor, Egypt. [dssb_sharing_buttons icon_placement="icon" icon_width="fixed" alignment="left" icon_color="#000000"...

What It’s Really Like to Spend 4 Days on a Nile Cruise – Review

A firsthand review of a 4-day Nile cruise from Luxor to Aswan. Early mornings, ancient temples, quiet sailing, and the strange feeling of watching Egypt pass by from a moving hotel.[dssb_sharing_buttons icon_placement="icon" icon_width="fixed" alignment="left"...